The three pitfalls that derail scaleups

Why fast-growing software companies get stuck and how to avoid these traps in your organization

Hi all! I hope you’re doing great. I returned from a one-week campervan vacation with a lot of energy, so here's another post. This one was triggered by a question I received before my vacation: how do my services compare to and complement classic Scrum training? It’s actually a recurring one that comes in many shapes (“Are you a software architect? Looks more like a coach / CTO / strategy role to me”).

I tried (again) to briefly describe the differences between solving challenges in the process dimension versus solving them holistically considering at least the process and the system dimensions (the potential client has set a new date for us to discuss my services in a couple of months, so there is an opportunity to apply this holistic consulting approach, working together with their Agile implementors).

Nevertheless, I also realized that, based on my experience, there is relatively little written material available on the topic. Most people follow approaches that attempt to solve challenges by considering only one dimension, leading to suboptimal or even worse situations. So I’m trying to shed some light on the topic. Hopefully, that’ll help me better describe what I do for a living.

The challenges in organizational scaling

Many experts have examined the challenges startups face as they grow beyond a small team of engineers (what people call scaleups). For example, I like the analysis presented in Martin Fowler’s blog, "Bottlenecks of Scaleups," as it identifies challenges that span multiple dimensions, including software architecture, people, and processes.

In this post, I’ll categorize the most common problems I’ve experienced in my career, depending on the dimension from which they stem. Then, I’ll share with you my advice based on my experience and what I’ve seen work. Keep in mind that these problems are not limited to startups; they’re also seen in bigger organizations when they start a new project or product.

The structure I’m using is simple. Essentially, in a software organization, you have these four key dimensions:

Business goals. This is how the organization defines success, e.g., monthly recurring revenue. Here, I also include the second-level goals, which are connected to these figures but take a first step in defining how to accomplish them from a product or service perspective. They form the product or service design, its “vision.”

System. The software that provides the product or service that the organization leverages to achieve its objectives. It should materialize the product or service design and vision.

Processes. This includes how people work together to achieve the organization’s objectives at multiple levels: how they design the product and its vision, how new ideas are mapped into functional increments, how those ideas are translated into system changes, etc.

Teams. The groups of people who work in the organization as (theoretically) independent units.

“Let’s hire more people. We’ll figure it out.”

The usual way for a startup to grow is by raising money from investors, who hope for a potential return on their investment (plus a gain) based on the promises made at the “Business goals” level. Those promises typically imply that the organization will hire more people to deliver more business value. If the business plan presented to investors is reasonably detailed, it might also include vague promises about how the other layers — systems (2) and processes (3) — will adapt to the new size of the organization. For example, a shiny migration of a monolithic architecture to microservices (system) or a brilliant implementation of Scrum practices (processes).

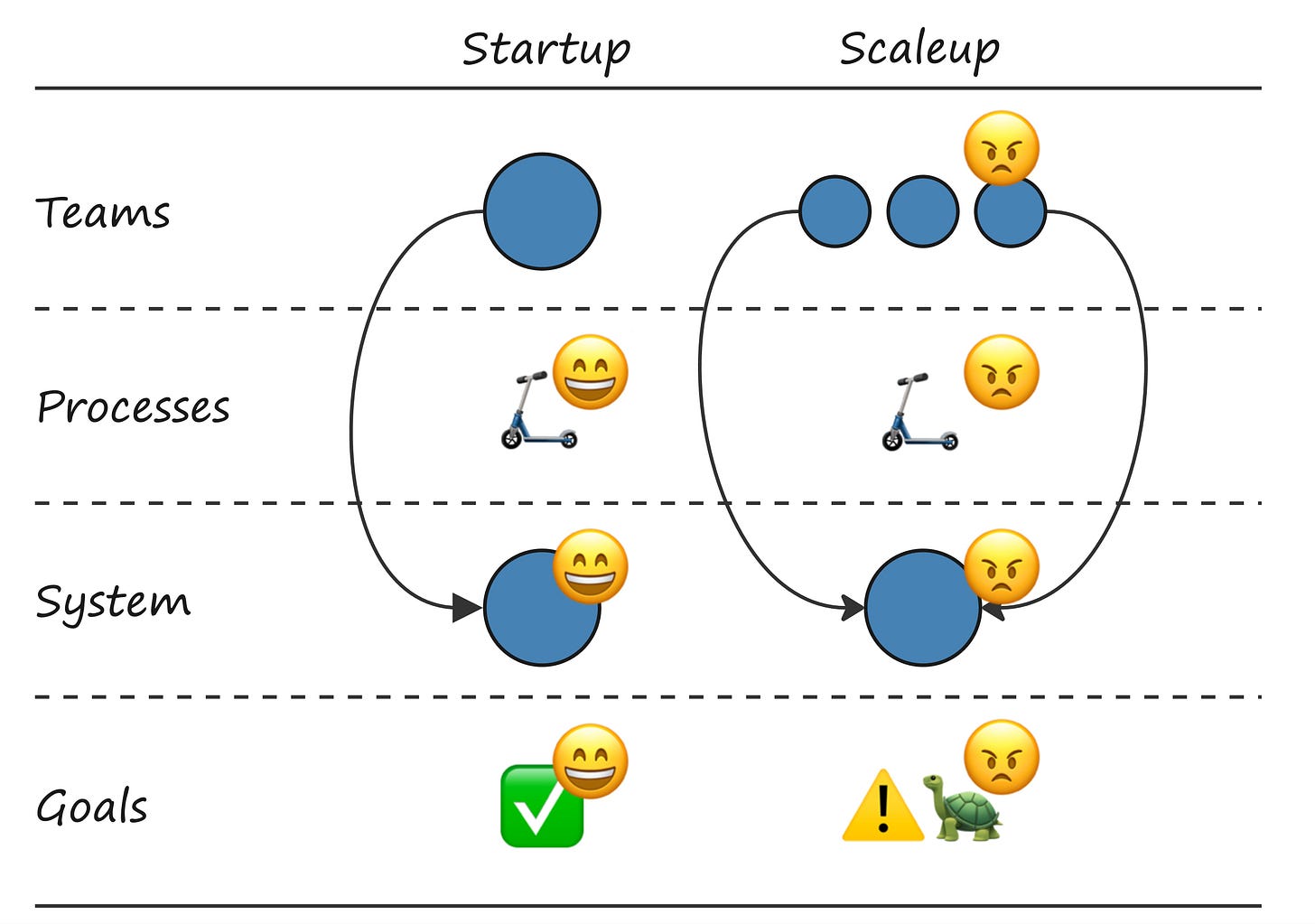

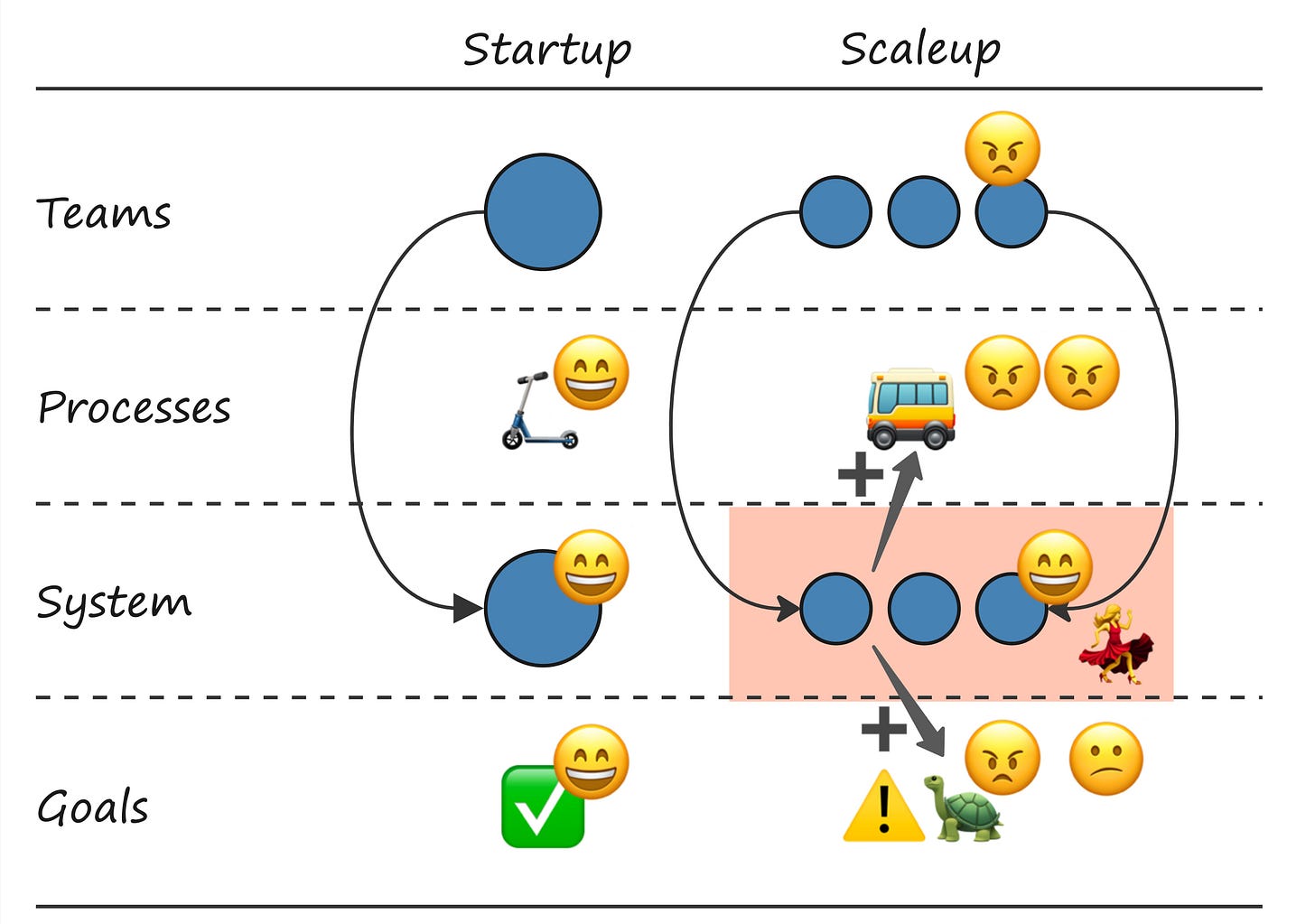

No matter the promises, at some point, the organization will reach the situation depicted in the following image, with some or perhaps all of its angry faces.

The business goals aren’t met, and there is an overall feeling that the organization is moving much slower than it did during the startup phase.

The system is a bottleneck due to its technical debt and inability to support multiple teams working on it, as it wasn’t initially designed to support organizational scaling (that wasn’t the goal).

Processes aren’t yet mature, and having more people without basic processes leads to confusion, a lack of accountability, and a lack of ownership.

The organization continues to hire people to meet the promised targets. Since the organization is in a semi-chaotic state, it attracts and retains people who like the freedom and space to create their own rules.

This end situation is a consequence of the first pitfall, which many people think is unavoidable. It would be very inefficient to try to accommodate the system, processes, and goals before hiring additional staff, wouldn’t it?

Pitfall #1: Hiring people blindly without having basic and realistic plans on how to evolve your system and processes.

You can benefit from some initial strategy, though. I’ll detail later how you can avoid falling into this trap.

Agile methodologies to the rescue!

The second pitfall is a classic consequence of the first, but it can also come as an independent initiative. In this case, as a reaction to chaos, the focus shifts to the processes. Managers typically lead the diagnosis, and they’ll read the symptoms as follows:

“We hired/have a lot of people. We’re not delivering as effectively as we expected to. This is due to…

We hired/have too many junior engineers and product people. They constantly depend on others (e.g., from the initial startup team).

Teams constantly depend on each other and are blocked, unsure of how to move forward.

Teams aren’t focusing on the important stuff. They don’t know how to prioritize the business inputs.

People don’t have an MVP mindset. They’re trying to build the perfect technical thing. They’re not business-oriented.”

I won’t enter into judging how accurately these symptoms are diagnosed, as each organization is different; however, these are common statements across organizations. In my experience, they’re over-simplified and deserve a Five-Whys method to dive deeper into the real pain points.

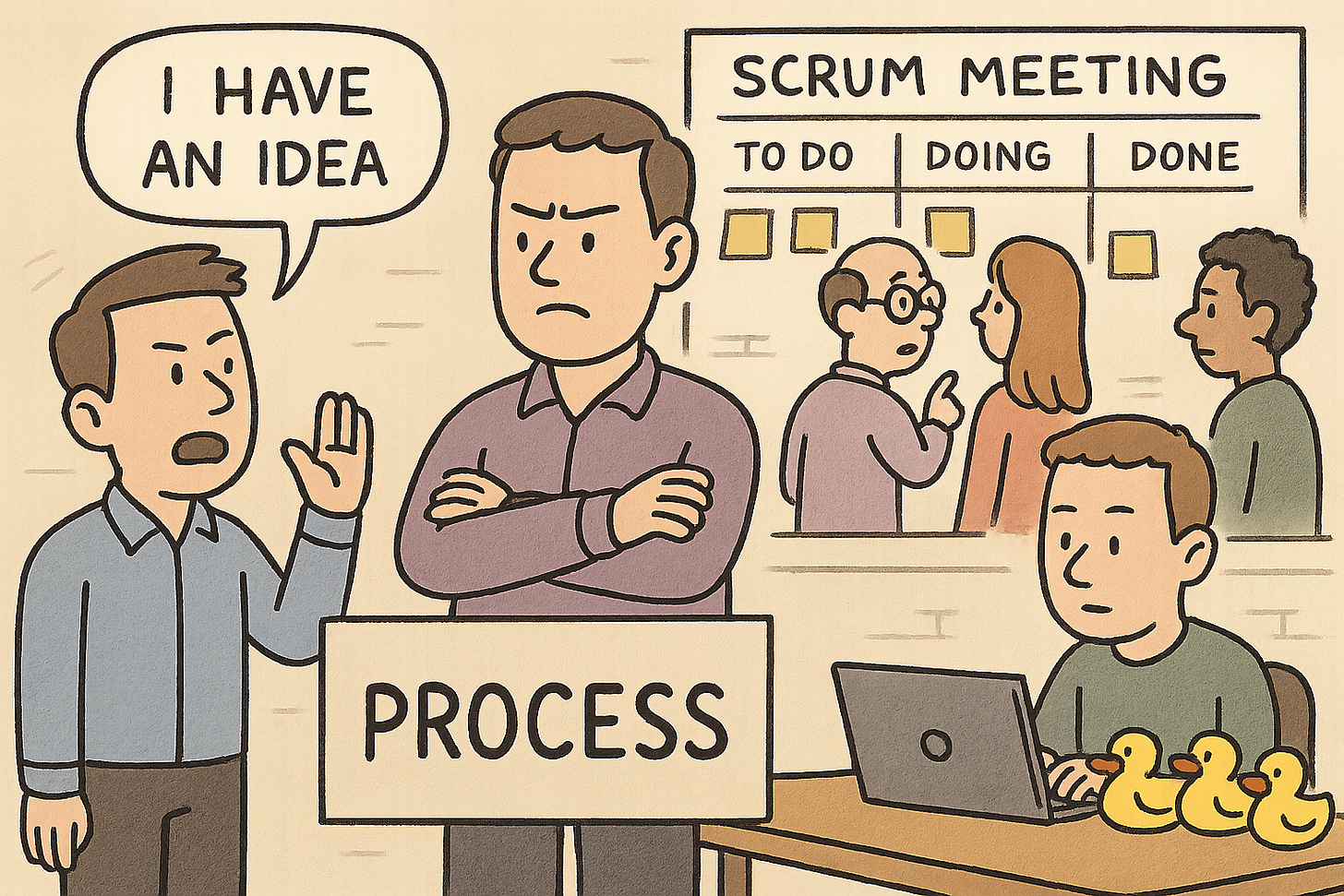

Most modern managers already know about Agile, so here you have two possible outcomes: getting to the conclusion that the organization needs to implement an Agile methodology if yours isn’t Agile yet, or changing its flavor if you already claim you follow an Agile approach (for example from plain Scrum to the infamous “Spotify model”). The promoters of this change will describe clearly how it can lead to improved ways of working and, therefore, solve the problems listed above. A funny variation of this situation happens when teams aren’t asked about the specific pain points at all, resulting in a missed opportunity to identify the real issues with processes and instead focusing blindly on solutions without first understanding the problems.

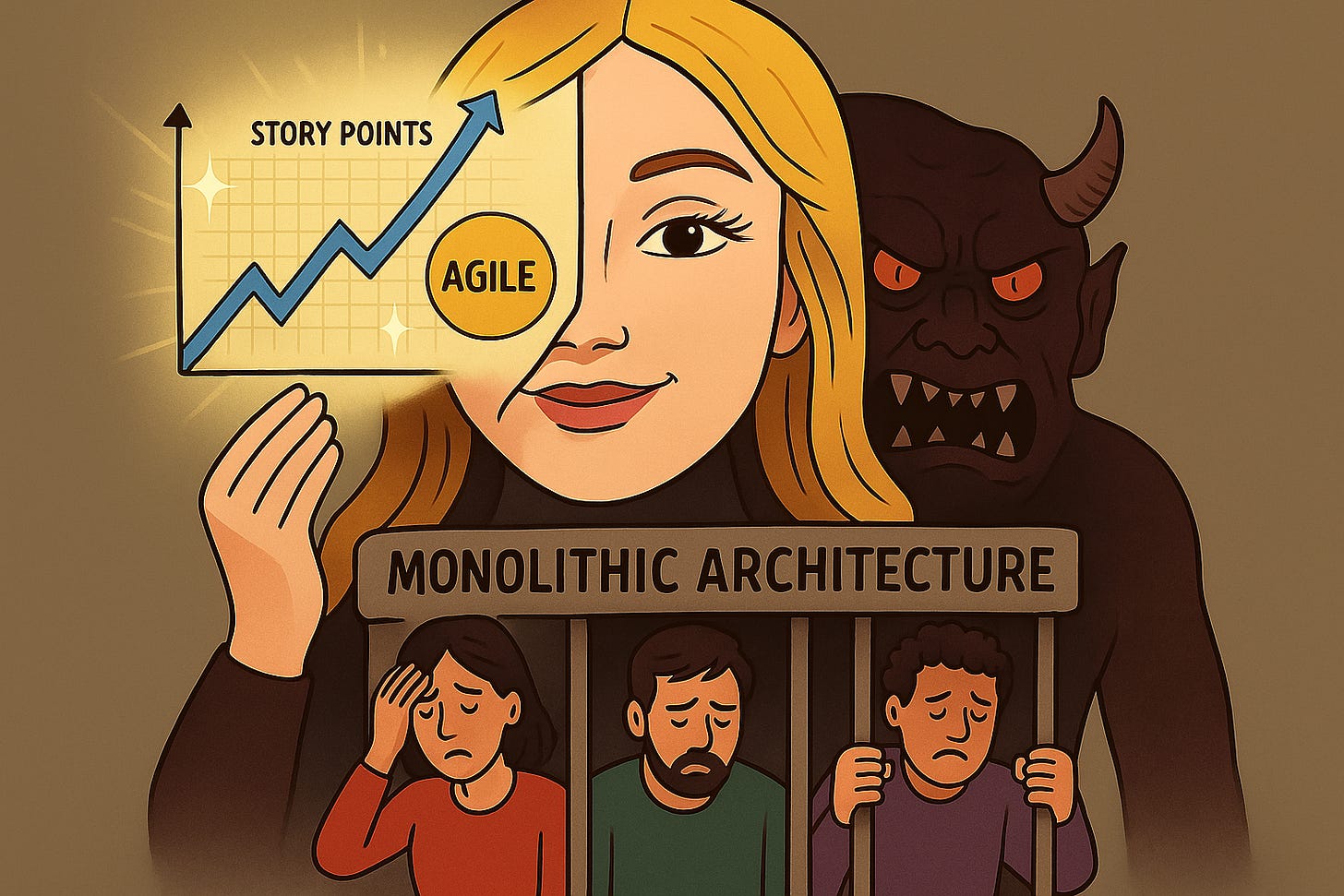

Then, in the best-case scenario, someone with experience in Agile methodologies is consulted (say, an Agile coach). This person, when presented with the problems and considering that the organization has no established processes, will, of course, agree with the advantages of implementing or improving an Agile methodology (see the Law of the Instrument). They’ll help with the implementation (in the worst-case scenario, people will try to implement whatever option on their own).

In any case, the Agile train departs. Let’s say it’s Scrum. Scrum Training? Check. Daily stand-ups? Check. Two-week Sprints? Wait, let’s better make it one week for faster delivery. Check. Retrospectives? Check. Sprint planning? Check. Refinement sessions? Check.

[Manager] You’ll be a Product Owner. You too. And you, so we have three teams, and we can parallelize more work.

[Product Owner] Hmm, what product do I own exactly? We only have one, the product.

[Manager] I’m not sure; you can figure that out. We can ‘adapt’ agile to our needs. Just ensure that you can pass tasks to this specific team so that they can implement them. We’ll track the delivery of story points to see how teams perform.

[Product Owner] Shouldn’t we measure the delivered business value instead?

[Manager] That’s not possible since we don’t have a mapping from teams to the business goals. Story points will do the trick for now.

Then…

[Manager] Who wants to be a Scrum Master? Let’s certify you and you, and we hire one external. Okay, now please focus on minimizing interdependencies so that each team is a self-organized unit.

[Scrum Master] Wait. We only have one product and a monolithic architecture. We’ll surely have interdependencies.

[Manager] Then we’ll set up a Scrum of Scrums structure. I’ll hire a scrum of scrums role. We can schedule a daily meeting right after the stand-up to orchestrate dependencies. We’ll create an epic to include the technical debt.

Sooner or later, depending on how smoothly you transition into becoming Agile, you’ll find out how you switch from not having any processes to a disguised bureaucracy.

The problems you had initially will remain:

You’ll deliver “faster” but in the shape of artificial increments that don’t have any business value.

The system will still be a bottleneck, and the technical debt can become larger if the Agile methodology is implemented in a short-sighted manner that doesn’t consider mid- to long-term system maintainability and other non-functional requirements.

Processes don’t come with accountability or ownership if the system, product- and technology-wise, hasn’t been properly split and its functionalities and/or components assigned to teams.

You keep hiring people and throwing them into the Agile mix. Before you realize it, you may end up implementing a scaled Agile framework (e.g., SAFe) without delivering significant business value, but keeping people engaged through roles, certifications, and processes.

You won’t go faster. You’ll go slower because you addressed one aspect of your organization without considering the others: the alignment of processes with the system structure and the business goals.

Pitfall #2. Implementing processes without having a basic strategy around the product vision and system architecture (what I call the content).

I’ll detail later how to avoid falling into this trap.

Don’t take me wrong; I like Agile principles and fully support them. The problem I’m trying to highlight here happens when an organization chooses a solution to improve its processes without considering other aspects at all.

Actually, there is also a popular variation of this pitfall where Agile is irrelevant. Another natural reaction to the chaos produced by onboarding many people into a project without a clear strategy for the system and alignment with goals is hiring more managers. Do people lack maturity? Hire a manager to fix that. Project ownership? Hire a project manager. Do we go too slow? Release Manager. Too much tech debt? Technical Program Manager. Too many engineers? Engineering manager. The resulting situation is exactly the same as described here, with the methodology replaced by the ad-hoc processes created by those management layers.

Microservices to the rescue!

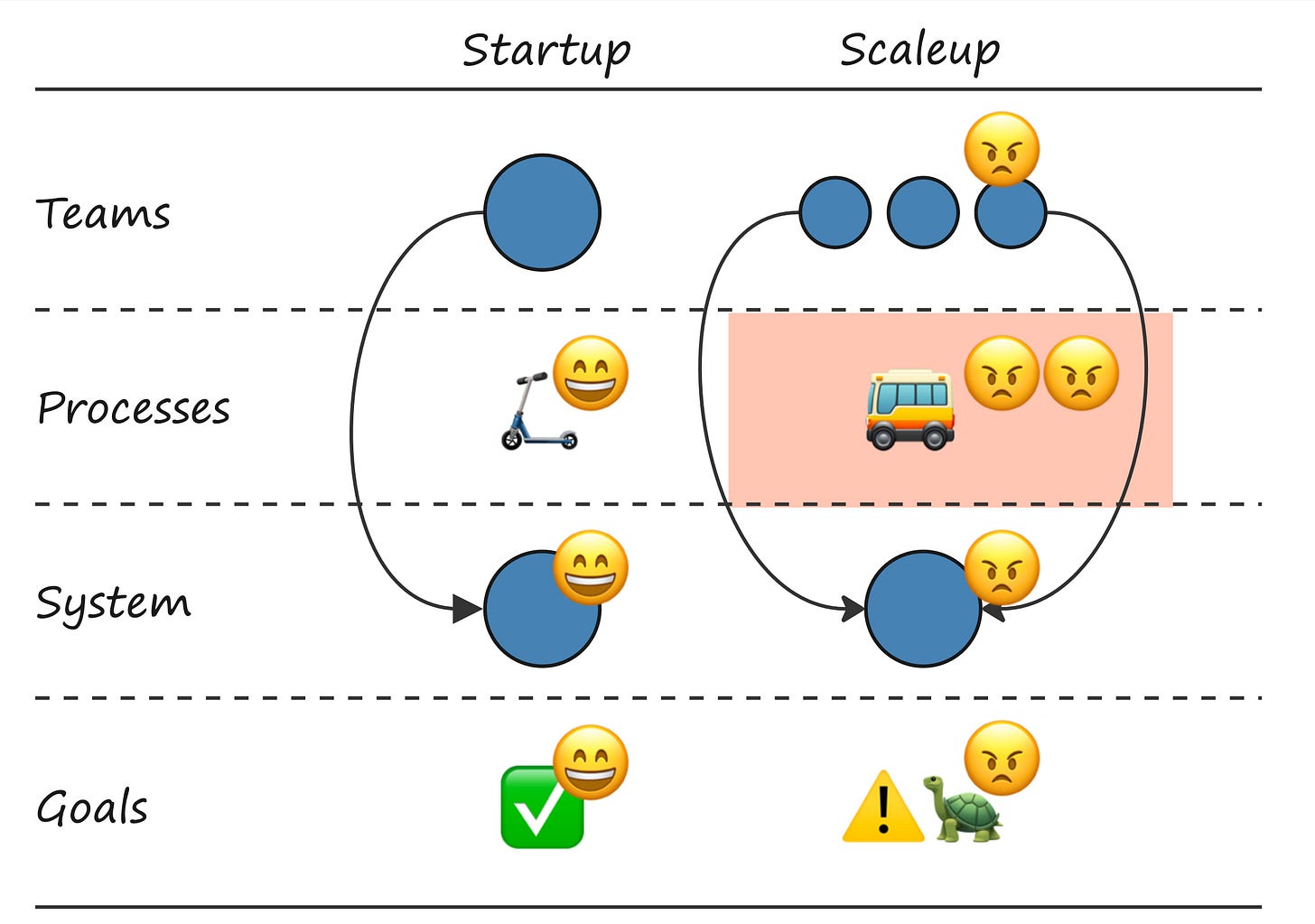

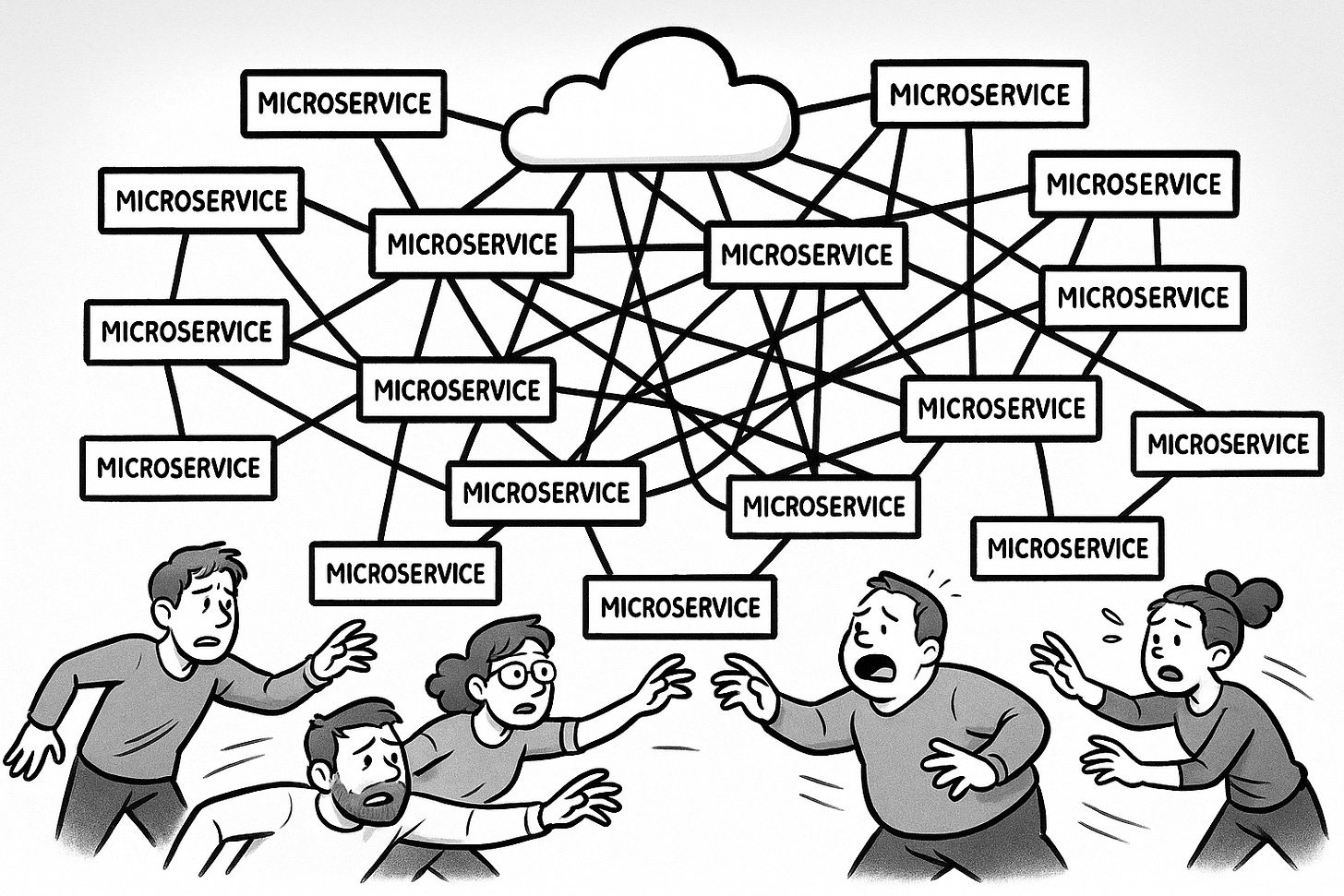

In organizations where technologists lead the scaling process, there is a considerable risk of ending up focusing too much on implementing complex software architectures like microservices, which typically come with event-driven approaches (with their corresponding eventual consistency), distributed transactions, CQRS, event-sourcing, and more fancy stuff if there aren’t any controls to validate how these architectural patterns will bring any business value advantages in the mid or long term. This is what I call a technical party.

Undoubtedly, a modular system offers the advantage of parallel work: new hires can work on different components or functional sections of the product independently, as they don’t share the same codebase.

They won’t suffer from technical conflicts, allowing them to move faster. Moreover, teams can be assigned to own these components (or modules or microservices), resulting in a certain improvement on the ownership and accountability side of things.

However, focusing solely on splitting the system without paying proper attention to aligning it with processes and goals can be disastrous as well:

An over-engineered solution, not aligned with business goals, will slow down the delivery of business value in both the short and long term, as it’ll make everything more complicated to implement and maintain.

If the technical strategy to split the system involves pure technical components (e.g., email system, frontend, authorization service), this means multiple teams may need to coordinate to deliver a new change in functionality, which typically spans multiple components. If the processes are not mature enough or aligned with this strategy, this situation will create even more confusion and frustration, slowing down the delivery as well.

Pitfall #3: Evolving the system to support organizational scale without considering how that impacts processes, and without aligning it with the business goals over time.

Again, I don’t have anything against microservices or modular systems. I wrote a book about the topic. I help organizations transition to those architectures to pay my mortgage. I hope you’re getting the point — one does not simply plan how to evolve the system, and everything else falls into place magically.

How to avoid these pitfalls

Surely, you know where I’m heading: balance. There isn’t a magic recipe that you can apply in an isolated manner to scale as an organization.

Let’s see, one by one, how to avoid falling into these traps.

Pitfall 1: Forcing growth by hiring more engineers

Solution 1. Stop hiring until you can prove an overall positive impact

The first solution sounds simple and obvious. If you can’t prove that hiring more engineers will have a positive effect on the mid to long-term, you won’t hire them, right?

It turns out that something as obvious can become complicated. Sometimes, hiring people is a high-level objective in the organization. The metric is as simple as the number of employees: “Our target, already committed to investors, is to grow the team this year by X engineers.“ Surreal. If you’re in this situation and you have the power to stop it, I recommend that you do it immediately. If you’re not in charge but have some influence (e.g., engineering manager, architect, senior engineers), leverage it and discuss the issue with the corresponding people to help them come to their senses. If the HR department’s bonuses are linked to these simple metrics, ensure that they are replaced with alternatives that make more sense.

What are good alternatives to the target “X number of engineers by [date]? Any metric that spans across the other key dimensions in your organization: Processes, Systems, and Goals.

❌ Onboarding success. You may claim to have worked on the onboarding process in your organization and conduct surveys to check how people experience it. But the problem is that being successfully onboarded in a team doesn’t directly mean being productive. This isn’t a good one since it only focuses on Teams.

❌ Customer growth. Hiring more people can actually help you acquire more customers, primarily if you work in B2B and hire more sales or commercial staff. However, this can create a massive tech debt that will ultimately destroy your organization in the long term. Here, you’re including the Goals dimension but neglecting the System and Teams.

❌ Released story points/features. This one is wrong for many reasons. For the scope of this post, it only focuses on Processes. The fact that you’re releasing more ‘points’ or whatever else doesn’t mean you’re faster achieving your organizational goals.

❌ DORA metrics. They measure the health of the system and the processes involved in changing and maintaining it quite well. However, you would be missing key factors on the Teams and Goals dimensions (again, having an excellent system doesn’t mean it’s aligned with the business goals).

✅ A combination of metrics that span multiple dimensions. As simple as that. You can have a dashboard and add people’s thoughts on top of it (since figures alone typically miss context). Form a group of representatives from multiple disciplines in the organization that can look at the current and potential future impact of hiring more people, considering the current state of your Goals, System, Processes, and Teams. You can combine metrics or voices that can give you insights about how smoothly your processes work (e.g., Change Lead Time), the team’s satisfaction (e.g., surveys), the technical debt and maintainability of the system (e.g., the remaining DORA metrics), and any potential change or update in the organizational goals (e.g., Customer Base Growth).

Pitfall 2: Changing processes will boost efficiency

Solution 2: Consider all dimensions of the organization when bringing new processes or improving them

This advice is based on the well-known principle that “what worked for organization X doesn’t mean it’ll work for your organization.” Additionally, I recommend that you pay special attention, holistically, to the current state of your organization.

Avoid copying and pasting processes from other companies, methodologies, and books. Start with some high-level guiding principles and iterate from there. You don’t need the entire Scrum framework with all its ceremonies to achieve faster, more business-centric releases in smaller increments.

When seeking a change in processes, align these changes with the existing constraints and their potential future impact on the systems and teams.

For example, say you have a ‘legacy’ organization structure where the three components of your system are assigned to three different teams. This is causing you trouble since complete features need to wait a long time because there is a dependency A→ B → C, and the three teams currently work in “silos” with their independent roadmaps. An effortless change that can boost productivity is to ensure there is a global roadmap with overall prioritization. A slight adjustment to the process that takes into account the current team's and system's shape. Then, inter-team dependencies can be discussed at that level and planned accordingly. You can also ensure good collaboration across teams by holding weekly sync-ups and maintaining open communication channels to check if there are opportunities for other team members to jump in and assist others. Sounds reasonable, right? You don’t need to restructure teams A, B, and C to become feature teams and shuffle people across them so you have expertise about all components within the same team. By the way, do you know what problem you’d be creating then? No one would own the technical components A, B, and C; you’d be diluting ownership and expertise.

Save the Scrum training and certifications. Go simple. Be inspired by methodologies and other ideas, but don’t follow them blindly.

Pitfall 3: Over-engineering systems

Solution 3: Always connect architecture (evolution) to goals, teams, and processes

In tech-driven organizations, there isn’t always good discipline to justify the technical evolution of the system. This is what you need to change. Why do you need microservices? Because you can improve delivery processes by enabling more parallelization, which in turn allows organizational growth. This is only a valid statement if the organization is growing, though. Alignment. Describe how. Check the real impact on overall indicators or insights.

The first step is to align the technology vision with the product vision and business goals. You can use simple methods, such as those included in the Software Architecture Vision tool. Once you have prioritized the technical principles and guidelines aligned with the desired non-functional requirements, you can define the system you need to accomplish that target (in the classic case where you aren’t there yet). Then, you develop a plan that strikes a good balance between delivering business value and evolving your system. You can consider patterns such as the Strangling Fig and Anti-Corruption Layers, among others. Elaborate your plan and connect with others to bring it to life.

Overall solution

Don’t seek optimization constrained to a single dimension of your organization, since that’ll be suboptimal and can even disrupt the others dramatically.

Look for a holistic solution, the global optimum, leveraging the knowledge you already have from different dimension’s representatives.

How is all this related to Software Architecture?

This is a clarification for readers who have reached this point in the post and are wondering why I’m writing about this high-level strategic topic instead of focusing on Software Architecture.

One of the key disciplines that can prevent the organization from falling into these pitfalls is Software Architecture. No matter if that function is represented by a person or a group of people and no matter the role (see The Invisible Architect).

Software Architecture is the voice of the System dimension. That means no process should be changed within the organization, no people should be shuffled or thrown into teams, and no goals should be shifted without discussing it with the Software Architecture representatives. This principle applies in the other direction, too: Software Architecture shouldn’t be changed unilaterally without having aligned with representatives from the different dimensions.

About me

Do you need help with these pitfalls?

As a Software Architect Consultant, I help organizations avoid these pitfalls and ensure they consider the System dimension when making relevant changes in the organization. I provide facilitation skills to connect and seek alignment with others, enabling us to find a holistic solution that considers all dimensions.

Let’s schedule a free consultation session if you need help. Contact me.

First of all, great article.

I can understand the confusion of your customers who expect Software Architect just fix software. I experience it myself while working full time for a company. Some people would say concerns you described are in the Enterprise Architecture domain, but Enterprise Architects discriminated the name, so probably we need new one 😀.